On the birth of Vietnamese fine-art history

Portrait of Mrs. Minh Nhẫn - Quỳnh Phụ district, Thái Bình province - 1804 - Gouache on paper - 120 x 77 (cm) - Vietnam National museum of Fine Arts - Hanoi, Vietnam

In 2024, I collaborated in a “pair” group project with a Chinese colleague on the exhibition Magiciens de la terre (Magicians of the Earth), curated by Jean-Hubert Martin at the Centre Pompidou (1989). This is considered the first exhibition in the history of modern art to address the issue of placing non-Western art on an equal footing with Western art, by exhibiting works and selecting 50 artists from the West and 50 artists from outside the West (Africa, Latin America, Australia, Asia, etc.).

At the time, in 1989, the exhibition attracted about 400,000 visitors to the Paris venue and an adjacent space.

The importance of this exhibition in art history is recognized, and in 2014, after 25 years, it was restaged at the Centre Pompidou. Notably, while Jean-Hubert Martin’s effort to blur the boundary between Western art (considered to carry the characteristics of colonialism and imperialism) is undeniable, the way he selected artists, displayed works, and organized side events (such as exchanges between non-Western artists and visitors) was criticized as entirely reflecting the “Western superiority” traits the exhibition was attempting to dismantle: – calling the artists “magicians” (implying spirituality or sorcery rather than creative work as a professional occupation) instead of artists; – selecting “craftsmen” from traditional cultural villages outside Europe rather than artists who had been and were practicing art in line with the contemporary global movements of the time (on the grounds that these local artists had been blended with and influenced by the West, and therefore were not truly original); – an exclusivist selection that exercised power in deciding who was allowed to be named or identified as an “artist” and what counted as “art” (in the fine art sense) outside Europe. These criticisms continue to exist in the field of art criticism today, and the exhibition is considered a “case study” for the curatorial field in exercising caution with “postcolonial” projects to avoid mistakes that carry the inherent colonial mindset in storytelling, creation, and practice.

Modernism is an ideology that emphasizes rationality, progress, and belief in the ability to transform the world through science, technology, and art in Europe at the end of the 19th century. This is also when art entered the period known as “modern art”—a stage deeply imbued with the ideology of modernism. In art, modernity is understood as the process of liberating art from tradition, seeking personal identity, and asserting art as an autonomous field—not serving religion, monarchy, or commerce. Supported by modernism, Europe and the United States carried out invasions and territorial expansion into Africa, Asia, Latin America, etc., under the mission of “civilizing” and spreading humanistic, civilized, modern values.

By the years before and after World War II, the wave of decolonization surged globally. Art entered the stage of contemporary art—emerging from the 1960s—but by 2025, many countries are still colonies of Western nations. Therefore, to this day, ideological and perceptual conflicts remain—especially with the explosion of the internet and easy access to postcolonial theories laid down since the 1970s by Edward Said, Frantz Fanon, etc.—and particularly the war in the Gaza Strip, which once again ignited debates and demands to reconsider concepts and ideologies with colonial character.

Since the 1990s, postcolonial issues have impacted all aspects of global economics, politics, society—especially art. The recent debate among Vietnamese artists, critics, and researchers on the concepts of Fine Art; modern fine art; contemporary fine art; and the role of EBAI (École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine) is of interest to me, even though this is not the first time I have read such discussions. But in 2025, marking the centennial of EBAI’s founding—and with quite a lot of sources “equating” or interpreting it as the birth of modern Vietnamese fine art or Vietnamese fine art itself—it becomes extremely important. And with this attention, perhaps we can “clarify once and for all”!

In the history of Western thought, many concepts were constructed not as natural or self-evident entities, but as the product of a particular historical ideology. Among them, “fine art” is one of the most complex and controversial concepts. While the term is often used to refer to art forms considered of high value such as painting, sculpture, music, or literature, few ask: where did the concept come from, how was it established, and who has the right to define it?

According to historian Larry Shiner in The Invention of Art: A Cultural History (2001), “fine art” is a cultural invention rather than an inherent essence of art. Shiner points out that before the 18th century in Europe, there was no clear distinction between the artist and the artisan, and art was understood much like the ancient Greek term techne—meaning skill or mastery.

It was during the Enlightenment, particularly through Charles Batteux’s Les Beaux-Arts réduits à un même Principe (1746), that the concept of “fine art” was established as a set of arts without direct practical function, intended to produce aesthetic pleasure and nourish the spirit. Batteux classified six types of fine art: painting, sculpture, music, poetry, dance, and rhetoric. Fields such as ceramics, weaving, carpentry, and stone carving—though requiring high skill—were excluded from the scope of fine art due to their functional nature.

From here, a system of division was established: fine art versus applied arts, decorative arts, and crafts. This laid the foundation for a hierarchical mindset in modern Western society: “pure” art associated with creative freedom, individual thought, and spiritual value; while “applied” art was seen as dependent on function, mass production, and lacking high expressiveness. Shiner points out that this division reflects class systems and cultural power: the “artist” becomes the free creative genius, while the “artisan” is downgraded to a hired worker. This was the beginning of a hierarchical aesthetic, legitimized through academies, museums, and patronage systems—and later by the nation-state and colonialism. Exported to the colonies, this system turned local artists into subjects of “civilization,” while defining what counted as “fine art.”

At the end of the 19th century, Europe entered modernism—movements such as Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Fauvism, Surrealism, Abstraction broke academic norms. Clement Greenberg, in Modernist Painting (1960), called for painting to “purify” itself by exploring its specific elements—flatness, color—rather than storytelling or depicting reality. However, this ideal of “autonomy” created a new system of exclusion: non-Western art, art tied to social function or ritual was considered “peripheral,” “premodern,” and fit only for ethnographic museums. For the colonies, “modern” was considered a universal value and imposed as a Western standard, obscuring the possibility of indigenous modernities.

Vietnamese fine art has a long history before directly encountering the Western concept of “fine art.” Ancient visual traditions such as Cham sculpture (2nd–15th centuries) with its own distinct style; Đông Sơn culture (bronze, drums, lost-wax casting techniques); Lý–Trần era art (Buddhism, reliefs, dragon and wave motifs; ceramics); or folk painting genres (Đông Hồ, Hàng Trống, Kim Hoàng) for both worship and decoration—all existed hundreds of years before the colonial period—demonstrating that a local fine art system had developed long before the 20th century.

In the early 20th century, the process of hybridization began at training institutions such as the Gia Định School of Fine Arts (1902) and the Thủ Dầu Một School of Arts and Crafts, which trained painting, sculpture, and decorative arts to serve decorative needs, posters, and colonial exhibitions. Works from this period include genre paintings, exhibition posters, and press illustrations, showing the combination of Western painting techniques with local subjects and forms. In the North, painters such as Thang Trần Phềnh and Lê Huy Miến also experimented with new styles before EBAI existed.

In 1925, Victor Tardieu founded EBAI in Hanoi, with Nguyễn Nam Sơn as teaching assistant. The school taught painting, sculpture, architecture to French academic standards, but encouraged the use of traditional materials such as lacquer, silk, and woodblock. Nora A. Taylor called this “indigenous modernism”—where Vietnamese artists learned Western techniques while seeking to affirm identity. Figures such as Lê Phổ, Nguyễn Phan Chánh, Tô Ngọc Vân, Trần Văn Cẩn, Nguyễn Gia Trí both participated in international exhibitions and formed a “hybrid” aesthetic—for example, silk paintings depicting village scenes using Western perspective. However, EBAI was not the “absolute beginning” of Vietnamese fine art or modern fine art, but rather a stage of institutionalization in an already existing tradition.

EBAI was an institution within the French colonial education system, under the protectorate government, part of the “civilizing mission”—the core ideology of French colonial policy. Publicly, it aimed to train local artists to French academic fine art standards, combined with “Indochinese distinctiveness” to create a hybrid style suited to the colonial image. At a deeper level, it aimed to “enlighten” and spread the culture of the “mother country” in three aspects:

1. Aesthetic enlightenment: Introducing Western art (drawing, perspective, anatomy, oil painting techniques, sculpture) to students;

2. Aesthetic standardization: Imposing the European standards of “beauty” and “high art”;

3. Promotion of French culture: Turning art into a channel to reinforce prestige and promote the image of a “civilized, generous France.”

The founding of EBAI also served political–economic interests: supporting colonial industries through applied arts training (ceramics, lacquer, interior decoration) for export; creating the image of a “civilized colony” through works displayed at colonial fairs; reinforcing power structures, shaping colonial identity as “both different and dependent” on France. As a result, EBAI trained generations of outstanding painters and sculptors (Tô Ngọc Vân, Nguyễn Gia Trí, Lê Phổ…), contributing to the formation of modern Vietnamese fine art; but the entire school model, curriculum, evaluation standards, and training goals served colonial ideology.

Over 20 years (1924–1945), EBAI trained hundreds of painters, sculptors, architects, including famous names such as Nguyễn Phan Chánh, Tô Ngọc Vân, Lê Phổ… They were widely introduced at international exhibitions such as the 1931 Paris Colonial Exhibition, in Rome, Italy, Belgium, and Japan. Le Monde magazine emphasized the school’s motto: “Un art qui a de la vie ne reproduit pas le passé, il le continue” (A living art does not reproduce the past, it continues it). According to J. M. Swinbank: “Tardieu’s academy gave birth to modern Vietnamese painting… many of EBAI’s aesthetic/technical models became hallmarks of Vietnamese modernism.” However, painting in Vietnam from the 17th–19th centuries, rich in aesthetic value, had already existed through portraits serving the wealthy, high-status class, using pigments on paper, formal compositions; serving commemorative, moral, and virtue-recording functions—quite different from “portraits” in European fine art, which were oriented toward individuality, emotion, and pure aesthetics.

Many countries outside Europe also have their own definitions and views of fine art, rejecting Europe’s classification. China distinguished literati painting from court painting, both using tools of craftsmanship; genres such as porcelain, jade carving, embroidery rarely bore the author’s name. Islamic art (Persia, Turkey, Mughal India) considered calligraphy the highest form, but artisans were usually court employees, not elevated to “individual genius” status as in the West. Yoruba art in Africa was tied to ritual, political power, and social meaning, but when encountered, the West often labeled it “artifacts” or “primitive art.” The clear-cut classification between fine art and crafts is a Western cultural construct, not universal worldwide.

From the 1960s to the present, a series of art movements and theories emerged, questioning the ideology of modernism: diversifying forms, reflecting on art itself, questioning identity—gender, race, geography; postmodern thinking rejecting grand narratives. Representative movements include Pop Art, Conceptual Art, Performance Art, Postcolonial Art. Despite promoting diversity, the global fine art system still maintains centralized power. Precisely in this period, the need to reinterpret values and concepts grew among non-Western artists and theorists. However, limitations in academic foundation, consistent practice, and global connections have kept their voices weak. There are still individuals who have shifted the field and been recognized by the West, such as Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor and Pakistani artist–critic Rasheed Araeen.

Okwui Enwezor (1963–2019) was a Nigerian curator and art critic, born in Calabar, educated in the US. He was the first Black and African curator of the Venice Biennale (2015) and also curated Documenta 11 (2002)—one of the most important events in postcolonial art history. Enwezor was the first to propose a multi-centered model in exhibitions, while developing theories on postcolonial modernity.

He identified four types of modernity:

1. Supermodernity: art commercialized through biennales and media, losing social context (e.g., in the US, Europe…);

2. Andromodernity: modernity linked to patriarchal social models, amplifying Western institutional, cultural, and economic frameworks but more dynamic due to rapidly developing economies tied to endogenous industrialization and urbanization (China, South Korea, India, etc.);

3. Specious Modernity: modernity imposed through Western models, leading to dependency (Islamic and Arab nations such as Syria, Iran, etc.);

4. Aftermodernity: where postcolonial communities that have NEVER EXPERIENCED the Western-defined modern era build their own modernities, characterized by decolonial resistance and identity struggles (Africa, etc.).

With these theories, Enwezor rejected the need for Western classification and recognition of modernity in non-Western societies—in other words, the modernity of non-Eurocentric countries is not the same as Europe’s modernity, and it is not that they lack their own modernity.

Rasheed Araeen (born 1935) is a Pakistani artist, theorist, and curator who has lived in the UK since 1964. He is the founder of Third Text (1987)—a highly influential postcolonial art journal. In his essay Our Bauhaus, Others’ Mudhouse (1989), Araeen questioned Bauhaus’ monopoly as the model of modernity in art and architecture—while indigenous architectural forms in Asia and Africa were dismissed as “non-modern.” He also criticized the Magiciens de la Terre (1989) exhibition—for casting non-Western artists in the role of “magicians” rather than thinkers. “We have always been modern, but our modernity has been erased by the Western system.” —Araeen, Third Text, 1993.

Both Enwezor and Araeen open a path: instead of seeking recognition from the center, it is necessary to rewrite art history from one’s own local context and knowledge. The concept of modernity we still use today—from art and philosophy to education—bears within it traces of power and exclusion. The theories, analyses, and curatorial practices of Okwui Enwezor and Rasheed Araeen not only help us understand global art more deeply, but also liberate thinking from the linear and exclusive logic of the West.

Nguyễn Quân is one of the first in Vietnam to criticize the understanding of fine art according to the Western model and to warn of the danger of copying form without grasping essence. He emphasized the necessity of redefining Vietnamese modernity from within, without dependence on French or Soviet models—as in “Modern Vietnamese Fine Art – Another Perspective” (published in various anthologies and journals), where he stated: “Modernity is an intellectual act, not a borrowed form.”

Recognizing the intellectual history of the concept of “fine art” is the first step to deconstruct what appears self-evident. From a concept born in 18th-century France, “fine art” became a global knowledge tool—not because it is correct—but because it was imposed through colonialism, education, exhibitions, and academia.

Today, when we question Vietnamese fine art, we cannot stop at adding “diversity of representation” for forgotten artists, but must:

– Rewrite art history from multiple centers, multiple timelines;

– View local artists as knowledge subjects, not merely cultural representatives;

– Reexamine the binary order between modern and traditional.

Only then will Vietnamese fine art no longer be considered peripheral to the mainstream flow of world art history, but as an independent case where history, culture, resistance, and creativity coexist inseparably. This requires many art theorists with a solid academic foundation, rich practical experience, language skills, and a calm, determined attitude to pursue these inherently demanding topics!

Hanoi, 10 August 2025

Phạm Thị Điệp Giang

Contested Frames: Authorship, Power, and Postcolonial Memory in the Case of the Napalm Girl

Captured from the WPP's website (https://www.worldpressphoto.org/news/2025/authorship-attribution-suspended-for-the-terror-of-war) on 16th May 2025

On May 16, 2025, World Press Photo (WPP) made a bold and unprecedented decision, reviving assumptions that seemed to have long been settled in the history of photojournalism. The organization officially suspended the attribution of authorship (https://www.worldpressphoto.org/news/2025/authorship-attribution-suspended-for-the-terror-of-war) of one of the most iconic photographs of the 20th century — The Terror of War, widely known as Napalm Girl. For more than five decades, the photograph had been credited to Huỳnh Công “Nick” Út, a Vietnamese photographer working for the Associated Press (AP). The photo, taken on June 8, 1972, during the Vietnam War, captures a group of panicked children fleeing after a napalm bombing in Trảng Bàng, particularly the nine-year-old girl Phan Thị Kim Phúc, naked and screaming in pain. This photo won the Pulitzer Prize and World Press Photo of the Year from WPP in 1973. It quickly became a symbol of the anti-war movement and one of the strongest visual indictments of the American war in Vietnam. However, in the context of new evidence and historical re-evaluation, even this photograph — long considered immutable in meaning and authorship — has become the center of a new debate.

The catalyst for WPP’s decision was The Stringer, a documentary released in early 2025 by The VII Foundation, which presented compelling arguments that the photographer may not have been Nick Út, but rather Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, a Vietnamese freelance contributor who also worked with AP on that day. More complex is the emergence of another name — Huỳnh Công Phúc, a Vietnamese military photographer who was also present at the scene, and who had repeatedly been misidentified in archival materials as Út. The film, supported by forensic visual analysis from the research group INDEX in Paris, used archival footage, positional data, and camera-type analysis to challenge the long-accepted narrative. Their findings pointed to many inconsistencies: Út appeared in footage standing farther from the scene at the decisive moment, while Nghệ was recorded standing closer, holding a Pentax camera with optical characteristics that more closely matched the disputed image. The investigation also showed that Phúc may have had a clear vantage point, raising the possibility that he was actually the one who took the photograph. As a result, World Press Photo concluded that while the photo itself is real and its impact undeniable, the question of its authorship is no longer certain. In the absence of definitive evidence to confirm Út’s claim or assign the photo to another person, the organization chose to suspend the attribution — but maintained the award granted to the photograph in 1973.

In contrast, the internal investigation by the Associated Press reaffirmed Út’s authorship based on archival records, including the original negatives, transmission logs, and interviews with surviving witnesses. Notable among them was veteran photojournalist David Burnett, who was present in Trảng Bàng on the day of the bombing and later worked at the AP office in Saigon, and who affirmed definitively that Út was the one who took the photograph, expressing concern that emerging claims were not supported by credible evidence. AP’s conclusion was clear: while they acknowledged new doubts, they found no convincing reason to revise the attribution and reaffirmed Nick Út as the author.

As a curator, I am drawn into this unfolding story not only because of its historical weight, but also because it raises a fundamental question that every serious photographer must eventually confront: who will be remembered, and who will be left in the shadows? Authorship in photography is often framed as a question of credit, but behind that lies a deeper structure of ethics, access, institutional power, and legacy. In this case, what began as an image of undeniable truth has turned into a multilayered investigation into the meaning of being an author in the world of visual storytelling, especially in a field where moments are captured amid chaos, where labor is often collaborative, and where the institutions that publish, award, and preserve images shape historical memory as much as the image-makers themselves.

The investigation into the authorship of the photo presented two different but somewhat overlapping perspectives, each shaped by the institutional interests and priorities of the organizations that conducted them. On one side is the Associated Press, a globally prestigious news agency that has defended Nick Út’s authorship claim since the day the photo was transmitted from Saigon. AP’s position rests on the principle of “burden of disproof” — that is, unless there is clear and irrefutable evidence that someone else took the photo, the original attribution should remain. For AP, this is not only a matter of factual accuracy, but also of institutional credibility, historical consistency, and the defense of a journalist whose name has become synonymous with courage and compassion. By upholding Út’s claim, AP also avoids a potentially damaging admission — that they may have misattributed one of the most influential images in modern history.

In contrast, World Press Photo chose a more cautious and ethically reflective approach. Instead of reaffirming what had long been taken as obvious truth, WPP emphasized new questions raised by forensic evidence and inconsistencies in the historical record. Their investigation found that Nghệ was likely better positioned at the time the photograph was taken, and that the image was most likely captured using a Pentax camera — matching the equipment Nghệ used, rather than the Leica and Nikon cameras Út typically used. Furthermore, new footage showed that Phúc was standing very close to the scene at the critical moment. With multiple plausible candidates and no definitive evidence for anyone, WPP made the bold decision to fully suspend the attribution. This action reflects an increasing awareness within institutions of the fragility of photographic truth and the dangers of oversimplification (a simplification often seen when the West looks at contexts from the Global South). It may also signal a shift in priorities within institutions like WPP — from protecting legacy to embracing transparency and critical reflection — in the context of a powerful decolonizing wave spreading across the global art world.

These seemingly contradictory conclusions — AP affirming, WPP suspending — in fact share many commonalities. Both investigations serve their own institutional interests. AP seeks to protect faith in its archive and the honor of a figure inscribed into the canon of journalism. WPP, by contrast, positions itself as an ethical standard-bearer for the evolving values of contemporary photojournalism — where admitting uncertainty is seen as more ethical than upholding a possibly flawed certainty.

From my perspective — a curator from Vietnam — I cannot avoid asking about the latent power in the act of “looking” and the hidden structures of authority behind the designation of authorship. While AP, as a major media institution and representative of the dominant power in media and art (especially at the time of the Vietnam invasion), has the power to impose standards and maintain its position in defining historical truth, World Press Photo, though more independent, is still a Western organization operating within ideologies and values shaped by the legacy of colonialism. Though different in form and stance, both organizations have the decisive voice in affirming or denying authorship, and thus profoundly influence how a photograph — and the person who took it — is recorded in history. Meanwhile, the three individuals who may be the author of the photograph — Nick Út, Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, and Huỳnh Công Phúc — are all Vietnamese, from a country once victim to colonialism and war, and in many aspects still in a weaker position within the global power structure. Nick Út’s lack — or inability — to speak out strongly to defend his authorship is not merely a personal action, but also reflects a deeper reality: the silence of an artist from a “voiceless” region when faced with a system of value assignment and remembrance controlled by the West.

In the history of photography, many similar cases of disputed authorship and erased collaborators have occurred. One of the most famous examples is the 1945 photograph by Joe Rosenthal, Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima (Pulitzer Prize for Photography in 1945, capturing six U.S. Marines raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima in the final stage of the Pacific War, taken by the Associated Press on February 23, 1945 and published in Sunday newspapers two days later), which was accused of being staged for decades. Though Rosenthal was vindicated, the identities of the soldiers in the photo were misrecorded for decades and only corrected through forensic analysis in the 21st century. Migrant Mother (taken at a migrant labor camp in Nipomo, California in 1936 during the Great Depression by Dorothea Lange, a photographer working for the U.S. Farm Security Administration [FSA], assigned to document the lives of farmers devastated by disaster and poverty to support Roosevelt’s New Deal welfare policies) — the woman in the photo with three children clinging to her became a symbol of suffering and compassion. The woman — Florence Owens Thompson — received no recognition or compensation and later spoke bitterly about her image being turned into a symbol of misery without her consent. Vivian Maier, one of the greatest street photographers of the 20th century, was only recognized posthumously, and her work and legacy are now shaped by collectors and curators — those who now control her archive. And countless collaborators, assistants, and local aides in wars from Vietnam to Iraq remain unnamed in captions and awards.

Returning to Napalm Girl, beyond what AP or WPP conclude, one truth remains: Nick Út is still alive, still observing, and still witnessing the ongoing re-evaluation of the moment that defined his career and international reputation. No detailed public rebuttal has been seen, nor any new statement clearly reaffirming his authorship in the face of these doubts — leaving a silent gap that causes many, including his admirers, to raise questions. For many Vietnamese people, especially photographers who have long seen the image as part of national memory and a source of professional inspiration, this controversy has not only opened a dialogue but may also have created a sense of disappointment or “a hollow feeling” (Vietnamese photographer Hải Thanh). It is unclear whether this is the feeling of watching history become uncertain, of seeing a once-solid legacy begin to shake under the weight of contradiction — or the ethical question of the photographer’s professional silence?

Whether the photograph belongs to Nick Út, Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, or someone else, its emotional impact remains unchanged — but its ownership, along with the narrative attached to it, is no longer a given. Therefore, the story of Napalm Girl and similar cases need to be more widely disseminated, deeply examined, and critically analyzed, not only as matters of photographic history, but as acts of critique, reflection, and decolonization of what we often take for granted as “historical truth.” Otherwise, history will always only be the story of the victors — and in the world of imagery, that victory includes the power to look, to narrate, and to be remembered. It also raises the question of how much symbolic weight we place not only on the photographer, but on the brand or tool they use — whether a Pentax is remembered differently than a Leica, whether equipment becomes part of the myth, whether technical prestige obscures our perception of authorship. What does it mean to credit a photograph when its creation was shaped by chaos, collaboration, or colonial dynamics? Should authorship be a fixed truth, or a recognition that can be shared (due to the collective nature of both the recorder and the subject being recorded/reconstructed within the work’s content)? Can we develop frameworks of attribution that even honor the context in which the work was made? And in an era where images are endlessly circulated, reused, and institutionalized, how can we ensure that justice is not only visual, but also historical? These are not easy questions to answer, but asking them is important and necessary — especially in a context where truths are becoming increasingly “hard to be true” amid the flood of falsehoods empowered by technology and the freedom of information.

Pham Thi Diep Giang

(Milan-based Vietnamese curator)

“Black Mirror” – A Decolonial-Spirited Exhibition by a Millennial Artist

Roméo Mivekannin's artwork after José de Ribera's La Mujer Barbuda (The Bearded Woman)

From March 9 to July 27, 2025, Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia presents “Black Mirror”, the first solo exhibition in Italy by artist Roméo Mivekannin – one of the standout figures in global contemporary art. Born in 1986 in Bouaké (Ivory Coast), raised in Benin, and now living between Toulouse and Cotonou, Mivekannin has attracted attention through numerous international exhibitions at venues such as the Sharjah Biennale, Zeitz MOCAA, Kunstmuseum Basel, and Musée du Quai Branly. His artistic practice delves into themes of historical memory, the role of imagery in constructing power and identity, particularly within post-colonial contexts.

The exhibition features around 20 new paintings created on black velvet—a suggestion from the museum based on a piece from its collection. This choice is both a visual and expressive challenge. Eschewing traditional canvases and frames, Mivekannin’s works are suspended, appearing to float in a darkened space, evoking a mysterious, almost metaphysical atmosphere. Black velvet does not reflect images but rather absorbs them, transforming the painting’s surface into a “black mirror”—true to the exhibition’s title—where images do not reflect light but instead absorb history, memory, and emotion.

A defining feature of Mivekannin’s work is his use of his own face to replace the figures in the paintings. This isn’t merely a form of self-portraiture but a politically and symbolically charged strategy: instead of perpetuating imposed historical imagery that marginalizes Black people, he inserts himself into the role of the subject, reclaiming a place once denied in Western art history. He inhabits figures from iconic works by Masaccio and Caravaggio, appears in colonial-era photographs, and even places himself in cinematic settings inspired by filmmakers like Pier Paolo Pasolini and Sergei Parajanov—both known for questioning the symbolic nature of imagery.

In his reimagining of Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of Saint Peter—a Baroque masterpiece marked by dramatic lighting, bodily tension, and emotional depth—the face of the soldier in the foreground raising the cross is replaced by Mivekannin’s own. His Black skin stands out against Caravaggio’s lighting, drawing attention to the historically sidelined presence of Black figures in art and religion—not as saints, but as burden-bearers. This substitution is both unsettling and declarative: the artist—a Black man—enters the canvas, no longer peripheral, but central to the image’s essence.

In The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, another Caravaggio masterpiece, Mivekannin intervenes to “rewrite” classical art through a contemporary and postcolonial lens. The original (1599–1600), housed in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, depicts a Roman soldier killing Saint Matthew at the altar mid-mass, amidst the horror of onlookers. Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro pushes light-dark contrasts to the extreme, underscoring human helplessness in the face of violence and fate. In Mivekannin’s version, rendered on black velvet, the scene seems enveloped in sacred darkness, where time and space hang suspended. As usual, he replaces the executioner’s face with his own. In Caravaggio’s composition, this figure is dynamic and muscular—central to the action. Mivekannin brings depth to this role through his gaze: direct, introspective, and haunting—flipping the dynamic between violence, victim, and executor. This prompts a tension in viewers: Who is the artist in this scene? A victim? A witness? Or someone compelled to commit violence to survive within an oppressive system? His substitution clearly reflects the decolonial message he pursues: not to illustrate history, but to interrogate it—disrupting European art history with a sense of unease. The black velvet—frameless, unmounted, suspended—transforms the painting into a theatrical veil or sacred symbol. The piece is no longer something simply to look at, but a space to confront and feel. Choosing a martyrdom scene by Caravaggio also carries powerful symbolism: it speaks not only of Saint Matthew’s death but also of the symbolic death of those erased from Western visual culture. Through this, Mivekannin performs an act of remembrance—not only for himself but for those never seen in the so-called “masterpieces.”

In his work inspired by The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden by Masaccio, Mivekannin replaces the faces of Adam and Eve with his own, adding a new layer of meaning: expulsion not only for sin but for race and exclusion from Western art systems. In a work based on La Mujer Barbuda (The Bearded Woman)—a 1631 painting by Spanish Baroque artist José de Ribera—the original depicts Magdalena Ventura, a woman with hirsutism, nursing her child with a full beard. This painting exemplifies the Baroque fascination with “the abnormal,” presented for aristocratic curiosity. The woman stands strong, unashamed, meeting the viewer’s gaze with pride and pain amidst judgmental stares. In Mivekannin’s reinterpretation, he does not replicate the full composition or supporting figures but focuses solely on the central character. Rather than keep Magdalena Ventura’s portrait, he replaces her face with his own. This is not a mere visual or technical gimmick, but a political and existential statement. By inserting his own face—a Black man—onto the body of a bearded woman nursing a child, he crafts a complex image brimming with ambiguity about gender, race, and the politics of the gaze. Ribera’s original reflects Europe’s “scientific curiosity and prejudice” toward difference—turning women into objects in a “cabinet of curiosities.” Mivekannin, however, reclaims subjectivity for the one being watched. Here, the figure is the artist himself—deliberately present, forcing viewers to face his gaze not as a freak but as a living symbol of transformation and emancipation.

In many of his works, Mivekannin retains historical compositions but alters the gaze: the character with his face stares directly at the viewer, shifting visual power from the observer to the observed, redefining perspectives on history from the viewpoint of those once sidelined.

The spirit of the exhibition is a resolute act of decolonization—quiet yet persistent—expressed through imagery, material, and the repetition of the artist’s face in forgotten, oppressed, or wounded contexts. Filmic influences like Holy Motors (Leos Carax) and The Color of Pomegranates (Parajanov) are restructured into visual compositions where bodily expression and eye contact create a silent but powerful rhythm.

More than a visual exhibition, Black Mirror is a journey into memory—where history is retold from a new point of view, where Black people are no longer shadows in the background but protagonists, storytellers, and mirrors reflecting a world being reshaped under the light of questioning and reconstruction.

Among recent contemporary exhibitions by young artists, Black Mirror is one that deeply excites me—for its themes, materials, and curation. My only concern lies with the preservation of the works, given that velvet requires meticulous care. The paint layers also risk peeling, as velvet’s fibers lack the cohesion of traditional canvases. However, the museum noted that several similar works in their collection, some centuries old, have remained intact—giving them confidence in long-term preservation. Even the exhibition’s postcards are thoughtfully designed: one side shows a piece by Mivekannin printed on paper, while the other features black velvet with exhibition details.

Milan, April 17th 2025

Phạm Thị Điệp Giang

#curatorialresearch #notesofthecurator #notesofanartist #notesofacollector #contemporaryart #decolonization

The Signature of an Artist

Photo: Le Pho's painting "The young lady in white dress" (1931) which was the only Vietnamese artwork to be shown at Venice Biennale 2024

1. An artist with a long history of creative work and recognition sometimes doesn’t need a written signature. At just a glance, even a young child can say, “This seems like a Picasso,” “This looks like Basquiat,” “This could be Rubens,” or “This resembles Van Gogh”—provided they have been exposed to art before. This demonstrates that a great artist with depth and an extensive body of work can be recognized through the content, composition, colors, brushstrokes, or the overall atmosphere of a piece, without the need for a written signature.

2. Artists have many ways to leave their “signature.” During the Renaissance, many master artists embedded their own images into their works. In Caravaggio’s Bacchus (1589), the artist’s portrait is hidden within the reflection of a wine jug. In The Arnolfini Portrait (1434) by Jan van Eyck, a Latin inscription resembling a garland above a mirror in the background reads, “Jan van Eyck was here.” Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens (1509-1511), a masterpiece of Classicism, features not only figures modeled after his real-life friends, such as Leonardo da Vinci, but also a curious face behind an arch on the right side of the fresco, next to Ptolemy and Zoroaster—it is Raphael himself.

3. In modern art from the 20th and 21st centuries, aside from written signatures, many artists use symbols as unmistakable personal marks. One of the most famous is the crown motif in Basquiat’s works. Alongside images of dinosaurs and skulls, his three-to-five-pointed crowns are among the most recognizable symbols. These crowns represent his desire to be “king”—a hunger for recognition and ascent—while also reflecting his admiration for artistic masters such as Leonardo da Vinci, Picasso, and Andy Warhol. The crown, symbolizing power, also embodies Basquiat’s internal struggle to create a sense of balance for Black identity and the lower social classes in a changing world.

4. When looking at works by early 20th-century Vietnamese artists living abroad, we see that, in addition to signatures and pen names, they often used personal seals. These seals served as an expression of their Asian heritage, a tradition, a habit, and even a form of certification. Some artists included both Romanized Vietnamese and Sino-Vietnamese characters in their signatures. In the 21st century, many young Vietnamese artists have revived this practice, or they stylize their signatures into graphic designs resembling seals instead of using conventional handwriting.

5. In art collecting, not all artists provide certificates of authenticity. Some artists avoid signing their work, fearing it might disrupt the composition. Others skillfully integrate their signature into the artwork itself. Some even have signatures more aesthetically appealing than the painting. However, collectors and buyers often still seek authentication. That said, not all artists issue certificates, and in some cases, they are unnecessary when the artist’s style, experience, and recognition are evident. For trained eyes, acquiring an artwork is more important than collecting a signature or a certificate. Sometimes, even certificates signed by family members of an artist can be questionable—ironically, they can be among the most skilled forgers!

6. A curious phenomenon today, particularly in Vietnam, is how some artists incorporate well-known and unmistakable signatures of famous international artists into their works. When encountering such “artworks” (or rather, “disasters”), I can’t help but feel astonished—for the artist, the collector, and even the journalists who write about them. What is the connection here? Inspiration? Imitation? Plagiarism? Theft? How does an artist justify using a globally recognized “signature” in their work? What does it have to do with their soul, their pain, their joy? And what about the collectors who acquire these works with unoriginal “signatures”? Are they indifferent? Ignorant? Uninformed? Or do they actually enjoy copies? Do they seek to imitate, to possess a “replicated” artwork?

7. A signature is also an identity. It is a legal affirmation of a person’s status and rights. In highly developed societies with strict legal systems, people rely solely on signatures rather than seals. Seals and certificates only arise when doubt and fraud exist. Given that there are billions of people in the world, it is exceedingly rare for two individuals to have identical signatures by coincidence. In the art world, identical “signatures” should not exist, and if they do, they are almost immediately deemed forgeries.

8. Artists, perhaps more than anyone else, value their “signature”—even more than their legal identity. It is the seal of their talent and professional integrity.

Phạm Thị Điệp Giang

July 6, 2024

The Beginning of the Year with the Appreciation of Antiquities

This morning, I have spent time admiring a ceramic lid from my antique Vietnamese Chu Đậu collection, with a diameter of only about 4 cm, likely dating back to the 14th century when Buddhism was still flourishing. The lid depicts an important episode in Buddhist stories—the dream of Queen Maya, the mother of the Buddha. According to the story, on the night of the Buddha’s conception, which coincided with a full moon in the summer, his mother dreamed that four celestial beings carried her to Lake Anotatta in Tibet. After being bathed and purified by them, a six-tusked white elephant appeared, holding a white lotus in its trunk. The elephant circled her three times before entering her body from the right side. Ten months later, she gave birth to the Buddha in Lumbini Garden, where he emerged from her right side.

The ceramic lid nearly perfectly illustrates this sacred vision of the white elephant offering a white lotus. Three lotus flowers and two lotus leaves are painted in a balanced and harmonious composition. Each lotus has eight petals, a well-known Buddhist symbol representing the Noble Eightfold Path, as well as the eight intrinsic characteristics of the lotus, which reflect the qualities of enlightenment: unstained (grows in mud but remains pure), purification (acts as a natural filter), patience (takes time to sprout from mud and bloom), perfection (maintains integrity, as the lotus seedpod is protected by petals), coolness (blooms in the hot summer, bringing refreshment like the nectar of compassion soothing human suffering), straightforwardness (grows upright from the mud), emptiness (hollow stem symbolizes detachment), simultaneity of cause and effect (blooms with its seedpod already formed, symbolizing the immediate manifestation of karma). By using this ceramic box in daily life, the story of the Buddha and the symbolism of the lotus are constantly recalled, unconsciously becoming ingrained in the user’s mind.

Art was originally created for religious purposes. Before the advent of writing, or when literacy was not yet widespread, humans relied on imagery to represent beliefs, myths, and sacred narratives. In Western history, art reached its peak with the spread of Christianity, particularly during the Renaissance, which began in 13th-century Florence and flourished in the 15th century. This period saw the use of oil painting to depict biblical stories. Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), an Italian painter, architect, art historian, and biographer of the Renaissance, authored Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. This work is considered the ideological foundation of Western art history and remains widely referenced in modern biographies of Renaissance artists, including Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and Michelangelo (1475-1564) . Vasari credited Jan van Eyck (139-1441), a master of the Northern Renaissance, as the father of oil painting. Western history and art textbooks also claim oil painting as a European invention.

However, a scientific article published by NBC on April 22, 2018 (https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna24261371) , provides concrete evidence challenging this belief. Research on the Bamiyan cave paintings in Afghanistan—found behind the two colossal Buddha statues destroyed by the Taliban in 2001—reveals that these artworks date from the 5th to 9th centuries and were created using oil-based paints. Experiments conducted at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility confirm that these paintings were made hundreds of years before oil painting techniques emerged in Europe. The findings, published in the Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry, establish these as the earliest known oil paintings in the world. Researcher Yoko Taniguchi states: “This is the earliest clear example of oil paintings in the world. Although drying oils were used by the ancient Romans and Egyptians, they were only applied in medicine and cosmetics.” Painted in the mid-7th century, these murals depict Buddhas in vermilion robes, seated in meditation amidst palm leaves and mythical creatures. Scientists discovered that 12 out of 50 caves contain oil-based paintings, likely using walnut and poppy seed oils as drying agents. This discovery proves that Asians, not Europeans, were the first to invent oil painting.

An Eastern proverb states: “There is always a higher mountain beyond the one we see.” This reminds us of the limitations of human understanding and the importance of intellectual humility. The vastness of the world holds many undiscovered truths, and countless pieces of knowledge remain unrecognized—either due to natural limitations in research or systematic control by dominant powers through funding and academic influence. The antiquities preserved in families, clans, and communities serve as records of cultural heritage, both material and spiritual. Exploring one’s cultural roots, ancient wisdom, and national history fosters intellectual independence—allowing individuals to understand their position and identity. Thus, the appreciation and collection of antiquities go beyond mere personal interest; they embody a refined sense of cultural preservation, a natural continuation of tradition, and a deep connection to national identity.

Pham Thi Diep Giang

Milan, February 3, 2025

Where to go and how long to travel to find home?

1. In Vietnamese, there are two commonly used words to describe movement in daily life, which are often interchangeable: “Đi” (to go) and “Về” (to return). However, when using “đi,” it carries an outward meaning, whereas “về” implies a specific place that is already known or previously mentioned, indicating familiarity. To make it easier to visualize, “đi” is like throwing a boomerang, and “về” is when it comes back. People usually say “đi ăn” (to go eat), “đi chơi” (to go out), “đi học” (to go to school), etc., but no one says “về ăn” (return to eat), “về chơi” (return to play), or “về học” (return to study), etc. People say “về nhà” (to return home), but no one says “đi nhà” (to go home), and when emphasizing the return, they combine both words into “đi về nhà” (to go home). At that point, “đi về nhà” encapsulates an entire journey: leaving and returning. With this compound phrase, it can sufficiently convey the meaning in English, whether as “home-coming” or “going home.”

2. Throughout human history—as a community, a species, and even as individuals—it has been a great journey of “Going” and “Returning.” This movement, for any reason: seeking shelter, food, escaping diseases, fleeing wars, natural disasters, spreading or protecting faith, longing for adventure and exploration of new lands, or pursuing freedom, has written grand, blood-soaked, glorious, bitter, or shameful histories. Many individual destinies have become blurred and nameless as they embarked on their own “going” and “returning” journeys. Among these, the journey to find a place called “home” is perhaps the most noble.

3. "This seekingfor my home ... was my affliction. ... Where is my home? I ask and seek and have sought for it; I have not found it" - Walter Benjamin in exile, quoting Nietzsche, 1939. Walter Benjamin—a German-Jewish philosopher and renowned cultural critic—born into a wealthy family in Berlin, was forced into exile due to the Jewish genocide, fleeing for eight years until deciding to end his life with an overdose of morphine in September 1940 to avoid falling into the hands of the Nazis at the French-Spanish border. At that time, his belongings handed over to the Figueras court included "a leather briefcase like businessmen use, a man's watch, a pipe, six photographs, an X-ray picture, glasses, various letters, magazines, and a few other papers whose content is unknown, and also some money." These “other papers” were later lost, leaving only his identity documents. This raises speculation about whether these might have been the lost manuscripts of “On the Concept of History” or “A Berlin Chronicle,” which were later published and became famous under the titles “Theses on the Philosophy of History” and “Berlin Childhood Around 1900.” Since starting exile not as a choice but as a necessity and an escape (his brother was executed in a concentration camp in 1942), Benjamin’s philosophical and personal reflections on history became an ongoing theme. As he admitted in “Berlin Chronicle,” homesickness was a primary motivator for his writing, hoping that “at least these images would allow readers to sense how deeply the writer had been deprived of the security that once enveloped him in childhood.”

4. The journey to find “home” and the desire to “return home” have inspired enduring artistic works. Known as one of the earliest ancient literary works still read today, addressing a journey home—it is the Odyssey, passed down orally from the 7th–8th century BCE. It recounts the 10-year journey of King Odysseus of Ithaca after the Trojan War, hindered by the sea god Poseidon from returning home.

"Nevertheless I long—I pine, all my days—

to travel home and see the dawn of my return.

And if a god will wreck me yet again on the wine-dark sea,

I can bear that too, with a spirit tempered to endure."

Many times, during their journey, Odysseus and his men wanted to abandon their desire to return, but perhaps that was impossible—because the story is a great metaphor for humanity’s longing to return home. As humans, who can live without family, homeland, or their country?

5. When "One Hundred Years of Solitude" was adapted into a film for the first time on Netflix in 2024, despite Gabriel García Márquez asserting that it was impossible, audiences were once again amazed by this famous story of the struggle to find a true home within our brief human existence, beautifully expressed through cinematic language. A home, a village, a land, even a country—all are built upon the search for a place of refuge. That refuge may be tied to the past or to sever it entirely, but even in arriving at a completely foreign land, we carry the memories and “artifacts” of past lives. Just as "One Hundred Years of Solitude" carries within it the hopes and despair of the ghostly town of Comala that follows

“There you'll find the place I love most in the world. The place where I grew thin from dreaming. My village, rising from the plain. Shaded with trees and leaves like a piggy bank filled with memories. You'll see why a person would want to live there forever. Dawn, morning, mid-day, night: all the same, except for the changes in the air. The air changes the color of things there. And life whirs by as quiet as a murmur...the pure murmuring of life.”

6. "I have gone home ... affectionately Marcel" -Marcel Duchamp in exile, 1940

On May 16, 1940, as Nazi Germany advanced on Paris, Marcel Duchamp left the city by train, heading south to the small coastal town of Arcachon, near Bordeaux. Despite being in an occupied area, Duchamp remained in Arcachon, trying to maintain a normal life. Since being forced to leave in 1940, Duchamp worked on his La Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase).

"The box contained a collection of sixty-nine reproductions of his own past artwork, which, begun in 1935, would be serialized an edition of more than 300, twenty of which were placed in leath valises. "My whole life's work fits into one suitcase," Duchamp would explain. By 1941, after completing the majority of reproductions, living conditions had worsened and Duchamp decided to leave France. But first he had to transport materials for his Boite from occupied Paris to the unoccupied south of France, where he could ship them off to New York. In the spring of 1941 he made three trips between Paris and Sanary-sur-Mer (near Marseille) where he had returned "home" (so he claimed) to the house of his sister, Yvonne. Disguised as a cheese merchant in order to cross through Nazi checkpoints and their travel restrictions, he shuttled a large suitcase containing material for the Boite, whose portable structure seems to have anticipated such displacement. (T.J. Demos - “Duchamp’s Box-in-a-Valise: Between Institutional Adaptation and Geopolitical Displacement”).

From this upheaval, the Box-in-a-Valise became one of the most famous tools, projects, and artworks of the 20th century. The suitcase not only contained replicas and miniatures of Duchamp’s works but also physical remnants of himself, reflecting a desire to preserve fragments of his life during exile, when a fixed refuge was unattainable. As Theodor Adorno noted, the Box-in-a-Valise “reveals the unfulfilled yearning for a home in an age of homelessness, for possessions when property is lost, and for independent existence amidst institutional domination, fascist control, and exile despair.”

7. In “The Arcades Project,” a monumental collection of writings about 19th-century Paris arcades (glass-and-iron-covered walkways), started in 1927 and unfinished due to his suicide, Walter Benjamin described collecting as a reaction to the fear of dispersion. More deeply, it revealed a nostalgic longing for home. Collections represented a “abridged universe,” a “nest,” serving a “biological function” of defense against the fragmentation of the external world.

"Perhaps the most deeply hidden motive of the person who collects can be described this way: he takes up the struggle against dispersion. The great collector, at origin, is affected by the confusion and the scattering of things in the world."

The collection’s space could also regress: the collector’s “box” symbolized "the originary form of all habitation" and the desire for it indicates "the human being's reflex to return to the maternal breast." Collecting, Benjamin argued, was not just about acquiring objects but compensating for the collector’s own fragmentation; its “biological function” drew the circle of the collector’s identity. Therefore, collections neutralized the “sitelessness” of decontextualization, even as collecting fueled the cycle of displacement from the start.

8. On Lunar New Year’s Day last year (2024), my parents and I went to the antique market outside Shi-Tennoji Temple in Osaka. I purchased two tea bowls with inscriptions from a reformed yakuza missing a finger. One of them, my father read to me, said “Clouds drifting, water flowing” (Mây trôi nước chảy). The year 2024 passed accordingly—like clouds and water, letting everything come and go naturally. On New Year’s Eve, now past 1 a.m. on the first day of Lunar New Year 2025, I began writing this piece to reflect on “Going Home.” Looking back, my journey across the world, my path to collecting, seems far from coincidental. Everything remains on its journey—not defining “home” by any specific place or location. Theodor Adorno remarked about Benjamin’s “Berlin Chronicle,” "For a man who no longer has a homeland, writing becomes a place to live." Benjamin himself had to split his mind into two—to distinguish the home tied to childhood memories from the home associated with national geography. "the feeling of homesickness was not about to overtake my mind. I attempted to limit it by becoming conscious of the irremediable loss of the past." as his homeland had become synonymous with fascism and Nazi persecution. "Just as the vaccine should not overtake the healthy body, the feeling of homesickness was not about to overtake my mind." It is indeed difficult to separate the personal space of one’s home from the collective space of one’s homeland or country when viewed from a distance, beyond its geographical borders. In a village’s bamboo grove, each house is a separate space measured in area. But for the displaced, “home” may be defined by skin color, language, or even the borders of an entire continent.

9.

“Remember when the Buddha was 80 years old and knew he would leave within a few months. He felt mcompassion for the monks, nuns, and friends, as many of them had not yet found a homeland. When hearing of their teacher’s passing, how lost and adrift we would feel.

…After the rains retreat, the Buddha made a final tour around the city of Vaisali, meeting monks, nuns, and lay followers practicing within his Sangha. Wherever he went, he gave short Dharma talks, only five to seven minutes long. The theme of these brief talks was often about finding a homeland. Knowing that after his passing, his disciples would feel lost, the Buddha said, "Friends, you have a refuge; you must return and rely on that refuge, and not on anything else". That refuge is the island of self, the Dharma, where there is safety, happiness, warmth, ancestors, and roots. It is called the island of self. In Pali, it is Attadipa. Atta means self, and dipa means island.

This is our true homeland, the island of self. There, the light of the Dharma shines, free from darkness. Return, and there is light. Return, and there is peace, security. The island is safe, untouched by the ocean waves… Returning to rely on the island of self is the practice. If any of us feel without a homeland, without a house, not yet arrived, restless, searching, still lonely… this is the method of practice. Return to rely on the island of self.”

(Thich Nhat Hanh)

Whenever I think of home and homeland, I recall this passage from Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh. It has followed me throughout my years of wandering (sometimes aimlessly). Perhaps this is why I love clouds—in Buddhism, they symbolize the Dharma. Nowhere lacks clouds, just as the Dharma is everywhere—with the Dharma, any place can feel like home, anywhere can feel safe and complete!

Phạm Thị Điệp Giang

(Milan, New Year’s Eve into the morning of Lunar New Year’s Day 2025)

A different curatorial project and unforgettable conversations

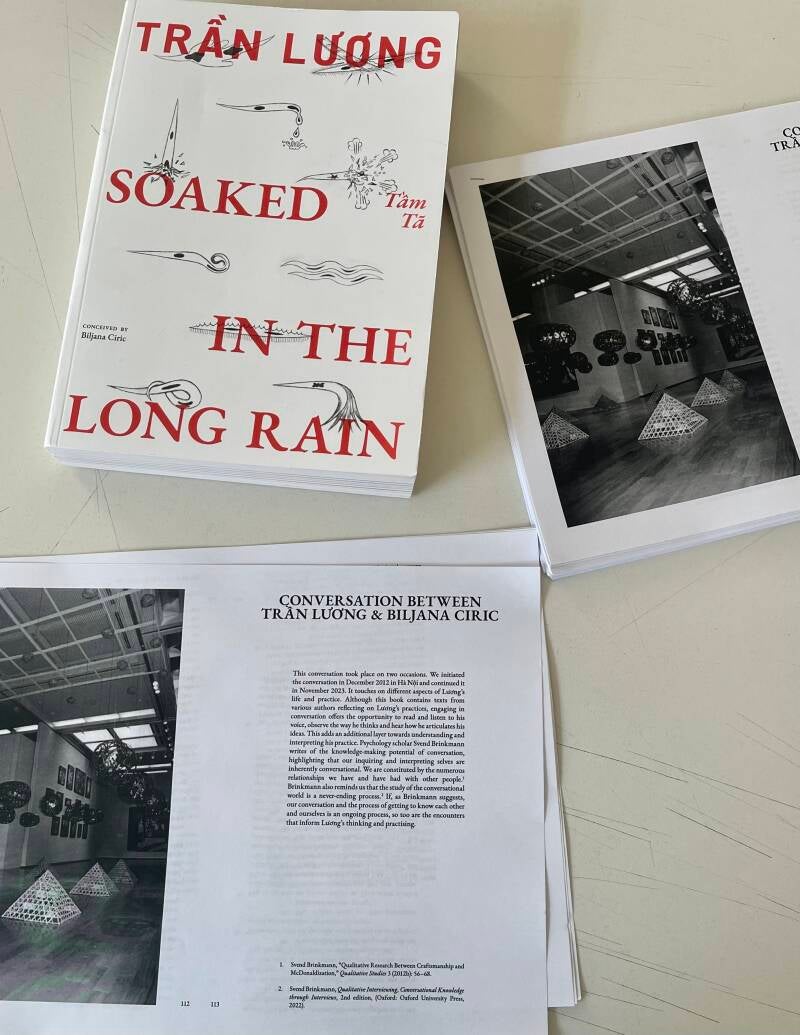

Today, I received an extraordinary gift – a promise from my teacher, Ilaria Bombelli, who is also the head of Publications at Mousse, a renowned Italian publishing house and magazine on contemporary art and culture with a global reach. She invited Biljana Ciric, the curator who “conceived” the newly globally released book "Trần Lương – Soaked in the long Rain" (published last month), which was completed in less than a week.

In the book I am currently writing about curatorial practices, I reflect on the first time I came across the term “curator.” That was also the first time I learned about Trần Lương, through Thể Thao Văn Hoá (The Sports & Culture newspaper) in the early 2000s. I don’t remember the exact details because, at the time, we were still reading print newspapers, and the internet was not yet common (in 2001, I was studying in South Korea, still using browsers like Netscape or Internet Explorer, and when I returned to Vietnam, I struggled with thesis materials stored on floppy disks). However, the word “curator” intrigued me—it seemed fascinating, unique, and a little strange. It stayed in my mind. I never imagined I would become a curator later in my career, initially through management roles in business, and now through formal studies. At that time, Trần Lương was almost the only Vietnamese name I associated with the profession of “curator.” It wasn’t until I moved to Saigon around 2007–2009, working and befriending people in the art community there, that I came to know others like Như Huy and Himiko Nguyễn—friends who were both artists and curators, opening art spaces, organizing exhibitions, and curating for young artists.

When I saw the book "Trần Lương – Soaked in the long Rain", I was immediately intrigued by its cover design. It combined symbolic drawings intertwined with the book’s English title and the artist’s name, prominently displayed with great respect, while the “author” was written in small print as “Conceived by Biljana Ciric.” This positioning suggested that the book is not just a conventional publication but rather a “portable exhibition” curated by Biljana Ciric for artist Trần Lương.

Before our conversation with Biljana Ciric, Ilaria shared with us a dialogue between Trần Lương and Biljana Ciric from two occasions: in December 2012 in Hanoi and November 2023. This provided insight into the artist and some of his works. This record has been vital for my research on the history of modern Vietnamese art. It partially answers a pressing question: Why is contemporary Vietnamese art not recognized in the broader context of global art? What factors have limited its development? Are the reasons external, or are they internal to the art industry itself?

In response to Biljana Ciric’s question, “When did you start playing the role of curator and organizing exhibitions?” Trần Lương shared:

“I tried to do some things between 1995 and 1998, but I think that period was more of a transitional phase for me. I was still learning and wasn’t clear on my direction. I increasingly felt that contemporary art could effectively express political and social issues. My opportunity to travel abroad came in late 1992 to early 1993, when I went to Europe—first to the Netherlands and then France. It was during that time that I began questioning why there was a lack of freedom here in Vietnam. Was it because of government pressure or did the local art community not know how to survive? What was the main reasong? It took me a few years to understand how I could help the art infrastructure in Vietnam.

By 1996 to 1997, I came to understand that Vietnam lacked the necessary infrastructure to support artists. In the Western art system, artists are surrounded by different professions that serve their needs such as curators, art historians, writers, art dealers, technicians, engineers, lawyers, fundraisers, and many others. Here in Vietnam, we had none of these…”

The dialogue delved into the context of the 1990s (Vietnam opened up in 1986 but only joined ASEAN and WTO in 1997, marking its real entry into globalization). It was around this time that international curators and exhibition organizers began appearing in Vietnam. However, Trần Lương noted that even then, “They didn't change the scene a lot. The Vietnamese presence at those international events was minor, so connections were not strong. One reason for this is that our scene consists mostly of artists; there are no art historians or writers to contextualize these experiences. Artists take what they can get. Another thing is that when artists travel abroad, they often spend more time shopping or visiting Disneyland than going to museums. We need to have a multi-faceted approach that includes perspectives from writers and art historians. Here, artists often feel isolated.”

Although Trần Lương was speaking about the 1990s and early 2000s, I believe his observations remain true even now in 2025. Of course, today, galleries, exhibition spaces, and the number of exhibitions and artists have grown exponentially—into the hundreds. Yet, in my opinion, over 90% of these efforts still serve purely “small” and short-term commercial purposes. Personally, while I don’t entirely resonate with the works from the “embassy art” period of the late 1990s–early 2000s in Vietnam, I must admit that when I participated in exhibitions, events, and performances in Hanoi during that time, I still vividly remember and long for the deeply immersive atmosphere of pure art. Back then, even with limited knowledge of global art, both artists and audiences were deeply engaged with the works. Performances at the Goethe Institute, L’Espace, spaces like Natasha Salon (which I found “weird” at the time :))), or private galleries around West Lake, as well as restaurants and bars, were always packed with artists and art enthusiasts. The discussions would continue into the night and spill over into online forums for months afterward.

What we still lack today, in my opinion, lies mainly in three reasons, which could easily be addressed:

1. We have many individuals with multidimensional artistic thinking and experience, but they face language barriers and lack the ability to express themselves—while those who actively “speak” and participate in art events are not necessarily the ones with sufficient awareness or expertise in the field (those who know don’t speak, those who speak don’t know). As a result, journalism or news about art often quotes general, vague, and superficial comments that lack a solid foundation or are commercially driven, focusing on the business side of art events as promoted by “speakers” (a very fitting term—it literally means “talkers”). Such comments are rampant in Vietnamese media but are rarely quoted in international professional art publications (because they are essentially meaningless), leaving us “invisible” in the global art context.

2. We lack, and severely so, professional and reliable art historians, art critics, and art writers—those who are competent, knowledgeable, and well-connected enough to publish credible and authoritative information in reputable art publications. Meanwhile, we have an abundance of culture reporters (and that’s where it stops!).

3. We are too “loving” and “harmonious,” which means almost no one criticizes or challenges anyone else’s works or exhibitions. The spirit of “harmony above all,” “each minding their own business,” or “friendly on the surface but not necessarily in agreement underneath” prevails in our art atmosphere. Everyone prefers praise over criticism and fears losing relationships. This reality leaves behind an overly “rosy” critical atmosphere, while actual debates retreat into private conversations over tea or drinks.

I’m not sure whether other Asian countries like China, India, etc.—where economies have developed rapidly, similar to Vietnam in the past two decades—are like this. Or what happened in Africa, where their independence timeline aligns closely with Vietnam’s reunification. What about Eastern Europe after the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991? One thing is certain: these regions have produced globally renowned curators playing pivotal roles in the world’s largest art events, such as Documenta or the Venice Biennale, and directors of national art museums in major art powerhouses—figures like Okwui Enwezor, the ruangrupa group in Indonesia, Johnson Chang, and WHW,...

This makes me think of the four types of Modernities that Okwui Enwezor proposed. Beyond the notion of Modernity (in art) as a universal value originating from Europe—a concept stemming from the Enlightenment in the 17th–18th centuries in Europe, particularly the French Revolution of 1789, which marked the end of European feudalism, the liberation of individuality, and was founded on three pillars: scientific rationality, private property rights, and the separation of humans from nature, granting humans the right to exploit nature as an infinite resource—Okwui Enwezor, a Nigerian curator who was the first Black artistic director of Documenta (Documenta 11, 2002) and the first Black curator of the Venice Biennale (2015, in its 120-year history), proposed four OTHER types of Modernities.

According to Okwui, in the Western world, especially Europe, curators and art practitioners are essentially “preserving” the corpses and artifacts of the past, as Modern Art (Supermodernity—the original and complete European form) there has already run its course. On the other hand, to witness truly vibrant artistic atmospheres, one must look to Asia, with rapidly developing economies like China, India, and South Korea. He refers to this as “Andromodernity”—a hybrid modernity where these countries import Western Modernity and replicate its operational formulas while striving to preserve their identities. In the Middle East or Arab countries, Okwui proposes the concept of Specious Modernity, where imported Modernity is only superficial, masking its true essence as authoritarianism, with examples like Iran, Turkey, and Lebanon. In Africa, the importation of Modernity from Europe is incomplete; Africa remains in a “primitive” stage, and Modernity in Africa is defined as “Aftermodernity”—a type of modernity that Africa itself will construct, rather than importing templates from Europe.

Against these four categories, where do you think Vietnam fits? And if we compare the three non-European Modernities, why is Africa currently prominent (e.g., the curator for the Venice Biennale 2026 is Koyo Kouoh, the first Black female curator of Swiss - Cameroonian)? Why are other Asian countries like India, South Korea, and China standing out, while the Middle East lags behind?

When asked how she came to the curatorial profession and connected with Asian artists like Trần Lương during a conversation in the MA program on Visual Arts and Curatorial Studies at NABA, hosted by Ilaria Bombelli, Biljana Ciric shared an inspiring and fascinating story. She stated that she didn’t study curation: “Even though I currently run an educational program for artists and curators, I moved to Shanghai in 2000 as a student in a field unrelated to contemporary art. However, upon arriving in 2000, I stumbled upon the contemporary art landscape at the time, which was still quite underground—a unique situation where exhibitions happened overnight in warehouses or private spaces. Experiencing these exhibitions was deeply captivating because I had never encountered contemporary art before. I began following the artists of that time, who were very bold in their curatorial practices. That’s why I always say that perhaps the most interesting and experimental exhibitions are often not organized by us curators but by artists. I learned a great deal from these practices, and I believe my understanding and approach to curation were largely shaped by those artists who were highly proactive in curating and publicizing their works because they had no other opportunities to present them to the public. And they were extremely creative in how they did it.

That’s how I started—very humbly, writing, knowing no one. I wasn’t the daughter of someone famous, nor the girlfriend of anyone in the group. So I reached out to a few art magazines at the time, most of which no longer exist. This was in the early 2000s. I began without a clear direction, not knowing where it would take me.

I must say, and I always emphasize this when talking about my curatorial work, that thanks to a special moment in China, my work took on an international dimension. That’s why I have the chance to speak with you today. It’s all thanks to China because, at that time, China was receiving significant global attention—everyone wanted to be part of China. Its booming economy and related fields drew the world’s interest.”

When Biljana Ciric described the “underground” contemporary art atmosphere in Shanghai in the early 2000s, it reminded me (Giang) of the period from 2007–2009 (interrupted by my two years of study in the Netherlands) and then from 2011 when I returned to Saigon. I participated in many similar “underground” art events in Saigon—where we had “marked” vehicles taking us to unannounced venues on the city’s outskirts. There, we would view works and performances by Vietnamese and international artists, including poetry readings, music, dance, drawing, and even nudity—experiencing the wildest creativity imaginable. The atmosphere in Saigon was clearly “underground,” lacking the kind of support from Western cultural and diplomatic institutions present in the North.

“You know,” Biljana continued, “I’m from South Asia, but China has always had a strong economic presence in the region. So from 2008 to 2011, I began conducting entirely self-funded research trips—no sponsors, no institutional support. I truly went there on my own, meeting people and making real connections. And yes, that was crucial because I often traveled with my boyfriend, and we had no money for hotels, so we stayed in the homes of artists.

The people in the region were incredibly hospitable. Artists often drove me to meet other artists and helped build connections.

In 2008, I made a trip to Vietnam, which was when I first met Lương. He was the one who connected me with artists in Hanoi. At that time, he was running Nhà Sàn. I remember he took me for lunch near a church and arranged for me to visit several studios. I had about a day to meet young artists working at Nhà Sàn and see their works. But what stood out was that he never really showed me his own works, which was very interesting. He simply helped other artists connect with me. Inever sat down with him to see his works on a computer or website, nor did we discuss what he typically painted. However, I maintained my relationship with him, and he participated in several of my group exhibitions. I also conducted a long-term research project on the history of exhibitions in China and Southeast Asia. One section of the book talks about the launch of Sàn Art, and I invited him to speak about his curatorial work in New Zealand—many of his workshops were held there.

During the COVID pandemic, a museum in Guangzhou invited me to curate a triennial exhibition because they recognized my long-standing relationship with the region. But you know, I was in Australia, and we were in lockdown. China was also in lockdown. How can you curate when you can’t connect, right? So, I decided to recreate several exhibitions from the region (Southeast Asia) for colleagues to experience as part of the triennial. From there, we continued planning this exhibition (at Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai). This is a long-term relationship. For instance, I conducted conversations with artists, which I always enjoy doing. I don’t think I should publish them immediately, so they remain stored in files. Regarding this region, I have many unpublished conversations. For instance, with Lương, I had a discussion around 2013, and we continued preparing for this exhibition afterward.

The title draws inspiration from the educational program Lương is running in Hanoi. Vietnam doesn’t have an educational structure for contemporary artists, like NABA or similar institutions. But he’s running a program called Tầm tã. I participated in it last year during a one-month stay to work on the exhibition and discuss the book for the first time. The program is open to artists, curators, and anyone wanting to experience art in a different way. It operates independently and continuously.”

I (Giang) was asked to explain the term Tầm tã, which I described as a vivid and evocative Vietnamese word. It can depict a person, landscape, or state of being, like persistent rain drenching everything in sadness and dampness. It also conveys a sense of overwhelming pressure and the difficulty of undertaking something challenging.

Biljana Ciric added that Tầm tã is also a kind of slang: “Lương said that if you stay out until 3 a.m. and friends ask how you feel, you can reply tầm tã to describe exhaustion, hardship, but also passion.”

To Biljana, "Trần Lương – Tầm tã – Soaked in the long Rain" isn’t merely a book. Creating it involved great effort, condensing images, information, and ideas into a book form. For her, it is a “mobile exhibition” where works by Trần Lương in various forms and periods are packaged and presented.